Le Versant noir - The Backside

〰️

Le Versant noir - The Backside 〰️

First French-English bilingual anthology by an Aboriginal/Wiradjuri poet

Excerpt

LE VERSANT NOIR/BLACKSIDE

FORWARD:

Certain minds can travel backwards and forwards to an age when spiritualities connect the continents through carefully crafted ceremonies invoking the higher reaches of humanity's consciousness. Poetry can, at times, be a substitute contemporary bridge of latent empathy, awaiting to be awakened to create a bond with other cultures, other Peoples, other religions, other spiritualities.

Kevin's authentic, brutally honest poems arise from the oral tradition of the Wiradjuri, a proud Nation straddling the Murrumbidgee, Kalara (Lachlan) and part of the Murray river basins. His poems speak universally across cultures whilst attesting to Wiradjuri's remarkable path of recovery from the genocidal onslaught of the British in the 1800s and the Australian successors’ intent on assimilating Wiradjuri and other Nations into an homogenous Australian society through social engineering and eugenics.

For many years there were only three published Aboriginal poets: Jack Davis, Kath Walker later known as Oogerroo Noonucal and Kevin Gilbert. Kevin's anthology ‘People Are Legends’ belongs to this period. To coincide with the heartless celebration of the scourge of colonialism, the 1988 Australian Bicentenary, which callously celebrated the 1788 beginning of the intended genocide against Aboriginal Nations and Peoples, we gathered poems whenever we crossed paths with a poet of this land. Kevin would obtain permission to publish and having typed out the handwritten wisdoms we collated the works into the first anthology of Aboriginal poetry, which Penguin Books published in 1988 as Inside Black Australia. It revealed seering truths from a consortium of voices needing to be heard. All of a sudden there were forty-four published poets. After that 'Aboriginal poetry' took off as an accepted literary form and now there are hundreds of First Nations poets changing the face of poetry from Australia forever.

In 1990 Kevin arranged for People Are Legends to be republished by Hyland House. He added more poems renaming the collection The Blackside: People Are Legends and other poems, in which his compassion and love for fellow beings focuses attention on larger-than-life personalities he highly respected - Uncle Paddy, Song to an Unrecognised National Hero: Alice Briggs of Purfleet, To Jacob Oberdoo, and In Memoriam: Pearl Gibbs. I had the privilege of typing many of the poems from the handwritten works scrawled on any available vacant space, backs of letters, the back of an envelope, even cardboard. Sometimes he'd be driving and ask me to scribe a poem, which is in the psyche for such a fleeting moment and needs to be captured without delay. Retyping from his handwriting evoked such a closeness to the pain in the emotion of the meaning that, at times, tears would wet the keys of the typewriter.

Believing that everyone is important, he found the humanity in each cameo that presented itself. As a channel for the voice of his people, he could forget himself and transfer his skill for others to be heard - Gularwundul's Wish, Metho Drinker, and Mum. He also reveals some of his own People's story in Kiacatoo, where a few of his ancestors escaped the murdering gunshot and survived a massacre by hiding underwater, breathing through a hollow reed acting as a snorkel.

In contrast he could be scathingly critical of his own people, those he considered to be agents of the coloniser, the sellouts, those too lame, too beaten, to raise a voice of opposition to their demise. He could slice them verbally as he does in To the Jackies I have met; The Collaborator; On Our Black Radicals in Government and semi-Government jobs, and The Better Blacks.

On the other hand, in Me and Jackomarri Talkin' About Land Rights, Granny Koori, The Flowering and Redfern he offers energising reassurance that the fight is not over; smoothing the dying pillow failed; the so-called 'vermin' were not all exterminated; inherent rights were not extinguished and that there is still time for people to rise up again and reclaim what is rightfully owned. He crystallises this in Speaking for Human Rights. In a sense he is handing on the baton to the generations to come in Look Koori as the positive changes are very slow in materialising. It is encouraging, however, that his long-held assertion that the sovereignty of Aboriginal Nations and Peoples was never legally transferred to the occupying power of the Crown, has taken root. One by one First Nations are making a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) demarcating inherent rights and freedoms denied if assimilated into the colonial Australian Constitution, which is still the 1900 Act of the British Parliament.

The Blackside includes translations of the original version of poems that Kevin had written in prison, but he had to vehemently disown the End of Dreamtime versions that were published before his release, because the editor/publisher bastardised the lyrical flow, reversed meanings and whole concepts were destroyed and derogatorily demeaned in the text he could no longer own. Here the magnificent poem Nomad is in its proper form and was selected by Kevin for the classic anthology The Blackside.

Kevin also used poetry as a potent missile, a weapon propelling the undiluted message in its pure form to 'heat-seek' its target and penetrate cracks in the belligerent consciousness of the colonial mindset that is so confident in its superiority, yet a dart of wisdom can trigger a fleeting moment of realisation that just perhaps the colonial construct is faulty; is wobbling on a shaky foundation; is unsustainable; is perpetrating genocide against the holders of the most ancient cultures on earth; is crippling human psyches long before they can reach maturity; is destroying the knowledge, hard-earned over millennia, of how the ecosystems are maintained and their components interact; is desecrating sacred spaces worshipped for the longest time on earth; is unforgivingly bombarding the mindset enveloping the necessary reverence for life that ensures biodiversity is enriched, a very different path and conflicting consciousness from the invaders' who still rape, pillage and plunder dragging the earth towards an unstable monoculture and dumbing-down the population into a moronic milieu divorced from the basic tenet of Respect.

Kevin held a mirror up to the wreckers of this magnificent world so that the perpetrators can see their reflection in the penetrating truths he committed to text in Shame, The Celebrators '88, Aboriginal Query - What is it you want, whiteman? and Baal Belbora – The Dancing has Ended – Now ask me whiteman, How do I feel? He reveals the colonial nature of the essence of appropriation - our Aboriginal heritage, our Aborigines.

As one of the major Aboriginal writers he led the way for others. In the words of Professor of Law, Irene Watson: “He left a paper-trail for us to follow.”

Vernon Ah Kee, a contemporary artist pays tribute: “What we know for sure, Because a White Man’ll Never Do It is an iconic book, Colonising Species an iconic artwork, Kill the Legend is an iconic poem, Cherry Pickers is an iconic play, Kevin Gilbert is responsible for iconic works in four disciplines. That is Kevin Gilbert. They’re iconic because he did them before anyone else did anything like it. He came along at least four decades before his time.”

At the end of his life Kevin reassured me that it was OK for his name to be used after his death. There was no need to silence his name from the colonial language since his Wiradjuri name is no longer voiced. He did not want his work to be forgotten just because no-one could say his name again. One of his favourite sayings is Omar Khayyam's:

“The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.”

Perhaps this reflects his belief that, however transient one's life is on earth, at least some wisdoms, ensnared by the embracing net of text, may linger and influence the positive potential of humanity into developing a contemporary society that nurtures Respect for every living thing and deeply values the gifts of Mother Earth, so that no longer is she raped and exploited by the extractive industries, but rather she is honoured for the sustenance and teachings she offers unconditionally. The Blackside, from which this anthology takes its title, elucidates the unashamed dignity in being Black, proud and belonging to this magnificent Country.

Having provided oxygen to keep the flame alive for recognition of Aboriginal inherent rights in this land, sadly Kevin died from his own lack of oxygen on 1 April 1993. Some of his ashes remain in Canberra at the Aboriginal Embassy, in which he totally believed to be the spearhead of the struggle for justice that is long overdue, and the remainder are at his birth place under a river red gum on the banks of the Kalara river, renamed the Lachlan river by the occupying power in honour of Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

Although I write from the vision of a different lens, it is still true to say Kevin is one of the most profound and challenging poets published in Australia. Tree is a classic in all that is best in poetry, written from trust in the strength of a synergistic human connection with the divine through physical channels that have sustained humanity's epic journey on this island continent through the ages.

In 2013, we exhibited a diverse range of Kevin's creative intelligence at Belconnen Art Centre in Canberra as part of the Centenary of Canberra. I Do Have a Belief honoured 80 years since his birth and twenty since his early death, displaying his rare talent in oils, acrylic, works on paper, poetry. Art has been the vehicle to tell many aspects of the struggle. With all but one of his books out of print we are making his work, his treasured vision for humanity, more widely accessible through the website https://www.kevingilbert.com.au.

Eleanor Gilbert

at 'Burrambinga'

Anembo, New South Wales

31 August 2015

Review

Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side , Le Versant noir

Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side by Joëlle Gardes - Terres de femmes

14 th year - No. 165 - August 2018 |

T d F

by Joëlle Gardes

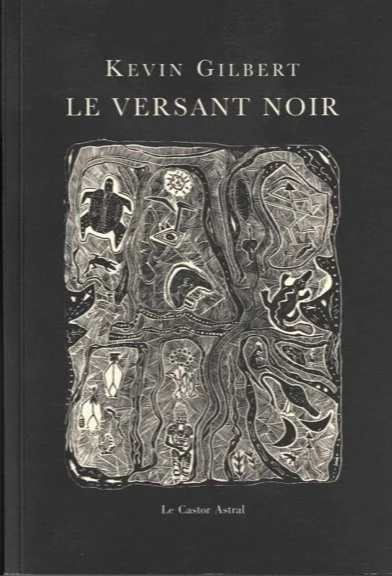

Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side, The People is legends and other poems, bilingual edition, The Astral Beaver, 2017. Translated from the English (Australia) by MarieChristine Masset. Foreword by Eleanor Gilbert.

Introduction of Kevin Gilbert. Reading of Joëlle Gardes

The Black Side is the title of the second poem of this beautiful and powerful collection. It gives its name to the ensemble, subtitled The People is legends and other poems. It is the voice of his oppressed people, that of the Aborigines of Australia, that Kevin Gilbert makes heard. As he explains in an introduction, which follows the foreword by Eleanor Gilbert (both give valuable insights into the poet's work), " The Black Sidecan be considered as a set of oral portraits of the oppressed, patriots, liberators, shouting their suffering and their determination in the winds of time. "The black slope," says the poem, "is the right slope," because it is the black color, the color of the skin of those whose rights and even their existence have not been recognized. In 1988, Australia celebrated the bicentenary of the establishment of the colony and it was on this occasion that the collection was collected. It was against the orders of King George that it was established without any treaty having been signed with the natives, terra nullius,nobody's land, so that the Aborigines, deprived of everything, never recognized colonization. Even if a partial restitution of their land took place, admittedly late, from 1976, even if the legal fiction of terra nullius was rejected, the slogan for a long time was "Australia with the whites", and the we know the sad story of children torn from their families to be assimilated, somehow whitewashed. Symbolic recognition took place in 2008 when the Prime Minister apologized for the wrong done to the Aborigines. Kevin Gilbert (1933-1993) had been dead for years.

Kevin Gilbert was a member of the Aboriginal Wiradjuri Nation, one of the 250 groups that occupied Australia prior to colonization. On the tragic situation of his people, he wrote many works

http://terresdefemmes.blogs.com/mon_weblog/2017/08/kevin-gilbert-le-versant-noir-par-jo%C3%ABlle-gardes.html 1/6

24/08/2018 Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side by Joëlle Gardes - Terres de femmes

of denunciation. The Blackside is the first of his works translated into French. We must thank for this translation the Castor Astral and especially the translator, Marie-Christine Masset.

In the texts gathered here parade several characters, real or symbolic, who speak like Uncle Paddy:

I am Paddy black. I pick the grapes And I catch rabbits

From one extreme to the other

Good fruit juice on my hands a week The other stinking intestines of rabbits

or to whom he addresses himself as "Hugh Ridgeway / Chrétien / Sobre / Noir / Décédé" ("Hospital Taree"). Or again, he describes the sufferings of this or that, humble or better known for his commitment, such as "On the death of a patriot", that of the activist Pearl Gibbs:

standing in force the patriots and the prophets are going to talk like Pearl did it for

precious life justice the people

Sometimes he is a traitor to the cause who is inviolated or harshly criticized:

Look at it my brother Look at the black climber [...]

Licking smiling lying Sucking the whites ... When children cry

And die days and nights

This committed, militant poetry, the antithesis of what is practiced here, gives a salutary shock. Never didactic, it is sometimes elegy, praise, diatribe, love poem, speech for the rights of man, but also often narrative. This also reminds us that poetry is not just meditation and that it needs flesh.

"Kiacatoo" describes the attack of a camp and the massacre of the inhabitants, "The desire of Gularwundul", the death of a little girl for lack of "clean water / flowing directly / of a tap in a can" which had been promised. The deplorable conditions of life or survival are widely evoked, all the more intolerable when they take place on the very ground of missions that should fight against them:

Of course the mission where I live is a dump Old huts that dogs sniff

Black babies dying in garbage

The white man is then caught: White man Come back to see the notch

What you did in the chest

http://terresdefemmes.blogs.com/mon_weblog/2017/08/kevin-gilbert-le-versant-noir-par-jo%C3%ABlle-gardes.html 2/6

24/08/2018 Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side by Joëlle Gardes - Terres de femmes

Earth by cutting the head of the Black

These poems practically without colors other than black and white, realistic and symbolic, show no pathos but express an immense anger at the "abduction of the country / theft and privations". In this sober and precise writing, from time to time, an image appears, striking: "your style / your colonial boot mask / your forked leg. "

In addition to the emotion that one feels in front of these retained but powerful texts, the interest is born from the realities and legends evoked. The aborigine terms abound, appropriately explained by the notes of the translator: the bora, place of sacred initiation, musical instruments, kylles and dijeridoos, the coolamon, small utensil that serves to transport the water ...

The-Dream-Time, Dreamtime, which refers to the lost golden age, "party long ago," is repeatedly reminded, for example in "My father's workshop," or in "Corroboree" the title of the poem designates the ceremony allowing the interaction of the Aborigines with this Time. The settler destroyed the legends, like that of Bunyip, mythical creature whose favorite prey is the woman, the "lubra", he broke the link with the sacred. This is one of the reproaches that the poet addresses to him in "The people are legends":

Kill the legend

The Massacre

With your atheism

Your fraternal hypocrisy [...]

For

To form the mold of a man At your level and your image White man

or in "Reversal":

greed and hatred are now the rule Where once did all sacred life

was loved

Compassion and anger arise from the description of the woman, the lubra, forced to "sell [s] a cat for a dollar" ("The other side of history"), in order to support her children or Jacky, the black man who abandons the dignity of his people and who drinks to forget, as most natives in the colonized countries did and do, starting with the Indians:

Give me a little piece for the pinard Brother

[...]

I'm not drunk by choice, I'm a black Brother

If I wanted to be drunk by choice Brother

http://terresdefemmes.blogs.com/mon_weblog/2017/08/kevin-gilbert-le-versant-noir-par-jo%C3%ABlle-gardes.html 3/6

24/08/2018 Kevin Gilbert, The Black Side by Joëlle Gardes - Terres de femmes

And sleep in the gutter

Not because I am a black man,

But by choice

Then you would have the right to sneer with contempt. ("Not chosen")

But beyond their circumstantial aspect, all the forms of oppression are denounced. The almost constant present, the absence of precise historical references, apart from a few poems, remove the text from a rootedness which is too precise, anecdotal, and gives it a universal value. And the form is essential here. In the simplicity of words and sentences, the density, the brutality of these poems overwhelm us, tear us away for a moment from our conformism and our egoism of haves. The beautiful and faithful translation, closer to the original, of Marie-Christine Masset allows to grasp all the hard flavor of the text and its scope.

The collection ends with the poem "Tree", but, more than a closing poem, it opens magnificently on a form of hope:

I am the tree

the hungry hard land

the crow and the eagle

the sun the gun and the sea

I am sacred clay

which forms the ground

the herbs the vineyards and the man I am all things created

I am you

and you are nothing

but by me the tree

You are

Joëlle Guards

D.R. Text Joëlle Guards for Women's Lands